Il Paragone

The history of portraiture

Lucy Fernandes

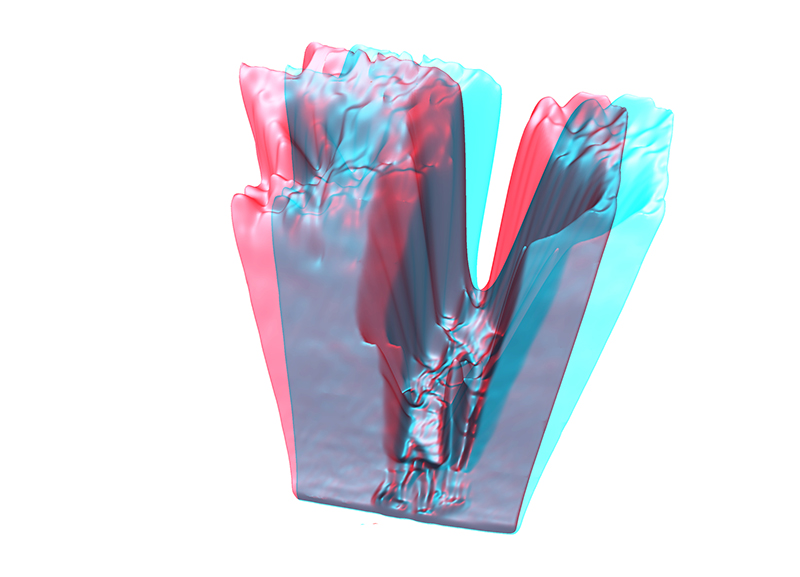

I was thinking about your piece in the context of the history of portraiture. Since the fifteenth century, the way that portraiture has been conceptualised in art historical and philosophical writing has been all about bringing the image of someone 'to life'; two important ones are (in England) Erasmus, who says that portraiture must capture the 'soul' of a person, and (in Italy) Alberti, who says that a portrait should make present an absent/dead friend, and there is always this tension between portraying the physical likeness or external appearance of a person, and evoking their inner character or 'soul' (which is not solid three-dimensional).

I'm sure Erasmus would have been delighted by the invention of photography, which at one point in its early history was actually believed to 'steal' a tiny piece of every person's soul when the photo was taken, and also catches them 'off guard', ie. captures their 'real' or 'true' self. Your piece fulfils Alberti's concerns even more: your work, like any portrait should, overcomes the physical barriers of time and space, bringing the three brothers 'to life' in your presence.

Alberti was also concerned with the issue of portraiture for how it fed into the paragone debate. In early Renaissance Italy, the only surviving classical examples of portraiture were sculpted portrait busts, which were colourless, inanimate, and a faithful record of external appearance, and no classical painting survived into the fifteenth century. However, the paragone debate goes back to classical times, especially to the writings of Pliny the Elder, who tells of the most famous Greek painter Apelles, who once painted the portrait of Alexander the Great. He says that Apelles' painting was so life-like, that once a bird tried to fly into one of his frescoes to peck at the grapes (presumably held by some Bacchus-like character). For the grapes to be life-like enough to convince an animal, they not only had to be rich in colour, but also look three dimensional, and modelled in light.

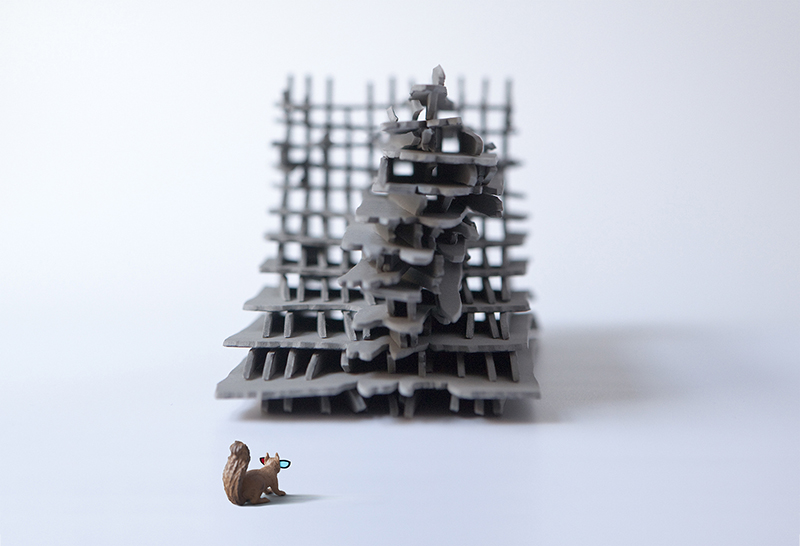

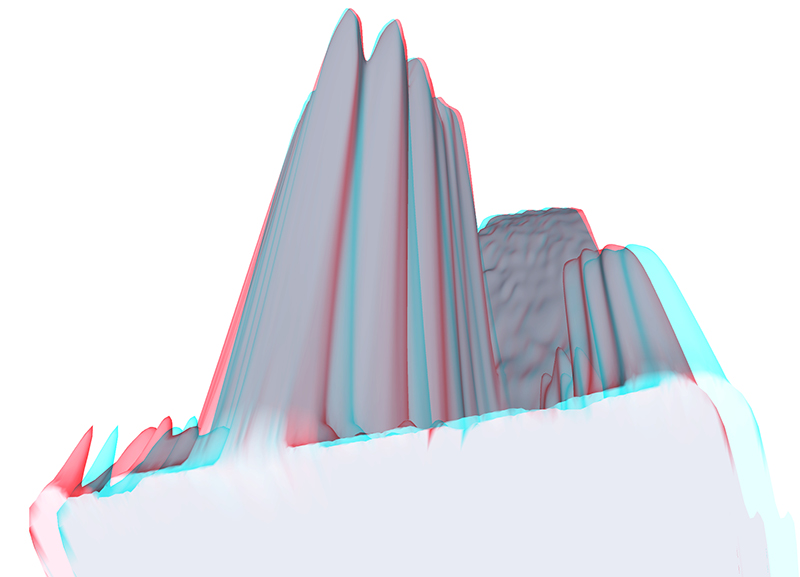

The story plagued the minds of renaissance thinkers and artists alike, who spent huge amounts of time and energy trying to emulate the achievements of Apelles. It put me in mind of your work, and whether a 21st-century squirrel might try and run into your painting to steal crumbs off the picnic table (he would need a mini-pair of 3D glasses though). To me the paragone debate, if taken to its polar extremes, can be mapped onto the subject-object dichotomy (as can everything), and your work aims to break down this distinction.

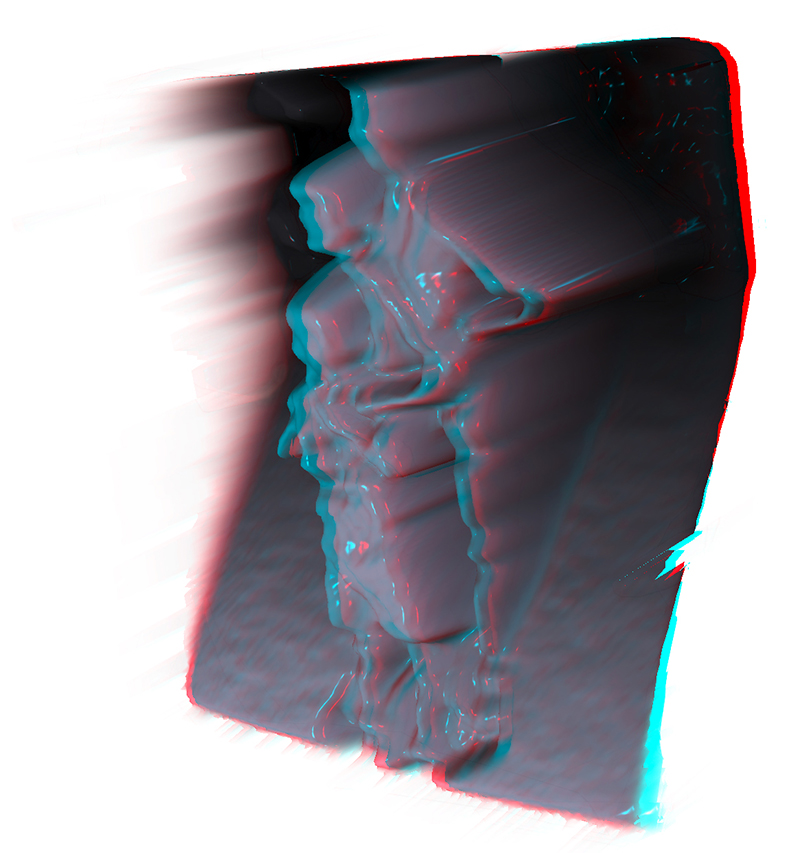

I was looking at your 3D model and the leg of your eldest brother. It made me think of Masaccio's Trinità in Florence, which is supposed to be the first example of proper perspective in Renaissance painting. Masaccio is kind of like the first real Renaissance artist, Renaissance being defined traditionally as the birth of perspective I guess.

Anyway it is fundamentally problematic because although the holy trinity (father, son and holy spirit) are depicted in a clearly-defined three dimensional space, when you look closely at the image you realise that God the Father, who is standing furthest back according to his feet is actually in line with Jesus and the donors when it comes to his head. It is directly under the pink arch. His feet would suggest he is half-way back into the coffered chapel-space. Say, three coffers in. Not quite so mathematically flawless after all. Anyway the 3D model made me think of it, and the placing of your brother's leg in the enlargement. His smile seems a lot closer.